Structure and Interpretation

of Tensor Programs

The Hacker's Guide to the Internals of Deep Learning Systems

Train nanogpt and nanochat by buildingteenygradfrom scratch, the bridge from microgradtotinygrad

Made with 🖤 by j4orz

Made possible by Lambda Labs Research Grant

First Edition.

Dedication

This course is dedicated to my father Dr. Thomas Zhang ND., R.TCMP, R.Ac

I owe everything to him.

In 2023, he guided me as my plans for graduate school were changed to helping my sister recover from mismanaged schizophrenia. That same year, he had two hemorrhagic strokes, and passed away shortly after. My personal relationship to the psychiatric mind and neurological brain led to a deep reflection on my life's work up ahead. The result is the following course notes and lectures.

I will make you proud dad. May you rest in pure land. We'll meet again. We’ll Meet Again by Vera Lynn 1939. Cover by Johnny Cash 2002.

Preface

As a compiler writer for domain specific cloud languages, I became frustrated with the non-constructiveness and disjointedness of my learning experience in the discipline of machine learning systems, particularly with domain specific tensor languages for training deep neural networks. The course notes that you are currently reading is my personal answer to these frustrations. It's

- inspired by interpreter (schemers) and compiler writers (mlers) teaching introductory programming with the canon of SICP/HTDP/PAPL/DCIC/OCEB. SITP carries that same whirlwind tour form but applies it to the substance of deep neural networks — while the fundamental data structure of SICP is the number, of HtDP the set, of DCIC the table, with SITP it's the ndarray. I've tried my best to write SITP such that however you feel about the previous books you also feel about this one.

- uses opensource code and explainers which globally sources the highest talent in the world. The deep learning framework

teenygradimplemented throughout the book shares 90% of it's abstractions withtinygrad, and is developed to such a point where it can run the training and inference of nanogpt. This makes it so the level of difficulty of the book and it's contents sit nicely between the "toy"-level which is too trivial and the "production"-level which is too complex.

Because the book concerns itself with the low-level programming of deep learning systems, we will be programming against language, platform, and architecture specifics. The teenygrad deep learning framework you develop throughout the book has a Python core for productivty, with CPU and GPU accelerated kernels implemented with Rust and CUDA Rust for it's amenability towards native acceleration. You are more than welcome to follow along with your own choice of host language implementation. For instance, feel free to swap out Python for Javascript1, Rust for C++, etc2.

With that said, the book has three parts:

- in part 1 you implement a multidimensional

Tensorand acceleratedBLASkernels - in part 2 you implement

.backward()and acceleratedcuBLASkernels for the age of research - in part 3 you implement a fusion compiler with

OpNodegraph IR for the age of scaling

If you empathize with some of my frustrations, you may benefit from the course too3. Good luck on your journey. Are you ready to begin?

-

Or combine the productivity and performance with

Mojofor instance! The world is your oyster. ↩ -

And if not, I hope this book poses as a good counterexample for what you have in mind. ↩

1. Elements of Learning

In part one of the book, we transition from the deterministic types of software 1.0 to the stochastic tensors of software 2.0

by training a house price prediction model with numpy's np.ndarray in order

to understand the mechanics of the statistical learning approach to artificial intelligence.

After that, we will implement our own multidimensional array for teenygrad with

teenygrad.Tensor, providing a multidimensional arrayBLAS-like kernels providing acceleration on multi-core processors like CPUs which we will then use to train a language sentiment model.

This will prepare us for the second part of the course where we change 1. the goal from learning price/sentiment to learning sequences and 2. the function class from generalized linear models to deep neural networks

Contents

- 1.1 Continuously Stochastic Software 2.0 with

scipy - 1.2 Regression: Learning Price Directly with

numpy - 1.3 Programming High Dimensional Data and Functions with

teenygrad - 1.4 Accelerating Basic Linear Algebra Subroutines with

teenygrad - 1.5 Classification: Learning Sentiment Iteratively with

teenygrad

1.1 Continuously Stochastic Software 2.0

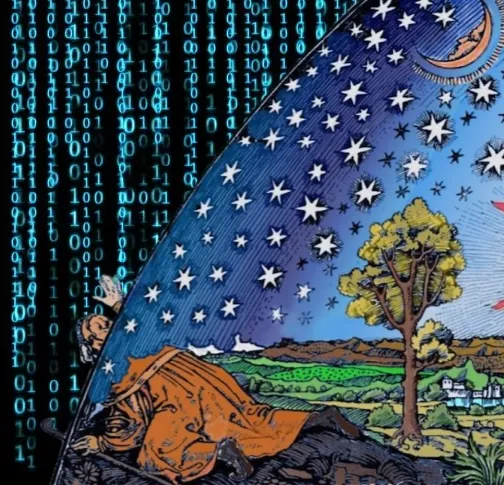

Although separated by 2000 years, the art of programming practiced in Silicon Valley shares the same dream as that of mathematics in Ancient Greece — that of discovering discrete descriptions of reality. While programmers prefer reducing all descriptions down to number (two natural numbers specifically, that of 0 and 1) while the mathematicians prefered reducing down to shape, what is shared in common is the preference towards the deterministically finite. Both programmer and mathematician use tools provided by toolsmiths referred to as interpreter/compiler writers and logicians: the programmer uses the values, types of a programming language, whereas the mathematician uses the proofs, and propositions of a mathematical logic.

Although the discipline of mathematics as originally started in Ancient Greece

shared unanimous discomfort in founding descriptions of reality in the continuously infinite

the usefulness of said descriptions became apparent as centuries passed,

with one prominent example being the so-called sunrise problem in which

many mathematicians switched from the deterministic tools of the proposition to the stochastic ones of the probability.

History is repeating itself for programmers are faced with the same challenge

with a new method of programming software into artificial intelligence.

This is the primary thread which will be pulled in this whirlwind tour of the Structure and Interpretation of Tensor Programs.

where train deep neural networks like nanogpt with our very own deep learning framework called teenygrad.

But to prepare ourselves, let's learn more about the sunrise problem which although appears estoric, may provide valuable insight

into how history is rhyming with itself.

1.1.1 Probabilities on Events with Set Theory

1.1.2 Propositions to Beliefs with Conditional Probability

(GOFAI -> machine learning)

1.1.3 Random Variables and their Distributions

- continous: gaussian (for regression) and exponential (for GLMs)

- discrete: bernouilli (for classification)

1.1.4 Statistical Inference: Probabilities from Data

- MLE of gaussian, exponential, and bernouilli

- MAP of gaussian, exponential, and bernouilli

1.2 Learning Price Directly with Regression in numpy

Although thus far nothing like ChatGPT has been discussed nor implemented, the generative nature of evaluating a probabilistic model and the inferring nature of inverting a function from data serves as the core foundation to the statistical learning approach to artificial intelligence.

Moving forwards, this essence of software 2.0's recovering functions from data continues to hold (in contrast to software 1.0's specifying functions with instructions) throughout the book, while the kinds of data and functions gradually become more complex. After part one, describing reality's fuzzy, continuous, and stochastic phenomena will become second nature, which is exactly what is needed to reproduce human-like capabilities of vision and language albeit with machines. In particular, the second part of the book 2. Neural Networks dives deep into the latter with large language models.

To obtain said foundation, the remaining chapters of part one cover

regression and classification and the implementation of high dimensional arrays.

In chapter 1.2 Learning Price Directly with Regression in numpy

a function of the form is learned from housing data

which can then be evaluated to predict the regressor of house prices with numpy's

high dimensional vector abstration np.ndarray.

Then, in chapter 1.3 Programming High Dimensional Data and Functions with teenygrad

and 1.4 Accelerating High Dimensional Functions with the BLAS

an accelerated high dimensional vector teenygrad.Tensor is programmed,

which is subsequently used in the last chapter 1.5 Learning Sentiment Iteratively with Classification in teenygrad

where a function of the form is learned from data

which can then be evaluated to predict the classifcation of language sentiment.

1.2.1 The Simplest Inductive Bias

The primary goal of the statistical learning approach to artificial intelligence is induction, which is to use data in order to make accurate predictions in new situations with some function . When there's access to historical data of the expected output for some input , we refer to this regime as supervised learning, for the learning algorithm is being "supervised" with the right answer.

In particular, the dataset is split into a training set , and a testing set . Once the function is recovered from the training set, it's ability to generalize is evaluated on the test set. that is, predict a value given some unseen observation . Machine learning has its roots in statistical inference, and so we also refer to the data as observations or evidence, and the function as hypotheses or models.

For instance, consider the task of house price prediction1 where the collected dataset are input-output pairs of square feet, and dollars, respectively. Let's take a look at this data.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

X, Y = [1500, 2100, 800], [500000, 800000, 250000]

plt.scatter(X,Y)

plt.title("Price vs Size")

plt.xlabel('ft^2')

plt.ylabel('$')

plt.show()

In the case of house price prediction, the input space is the size in square feet, and the output space is the price, which means the function to recover has type . Since enumerating through every house size and price pair in is intractable (otherwise all pairs could be inserted inside a lookup), an assumption about the structure of the data needs to be made, referred to as the inductive bias. The simplest assumption to make is to assume that there exists a linear relationship between the data so that is determined by two parameters of slope and intercept . That is,

where is used to denote the differentiation between input and parameter2.

Implementing computable looks like the following,

where each evaluation of fhat() passes in a random number for the slope parameter of x.

Feel free to modify the range for and run the code a few times to see the different values fhat() produces as predictions.

def fhat(x: float, m: float, b: float) -> float:

yhat = x*m+b

return yhat

if __name__ == "__main__":

import random

X, Y = [1500, 2100, 800], [500000, 800000, 250000]

m, b = random.uniform(-3.0, 3.0), random.uniform(-3.0, 3.0)

for (xi,yi) in zip(X,Y):

yihat = fhat(xi,m,b)

print(f"expected: ${yi}, actual: ${yihat:.2f}")

And instead of evaluating fhat() for each input xi sequentially in a loop,

we can change the type of the input from a scalar to a vector

so that the predictions can be evaluated in a single vector-scalar multiplication

(and subsequently vector-scalar addition) where

Some languages are adding support for multidimensional arrays in their standard libraries (todo, footenote with cpp),

but all numerical computing in python which involve the evaluation of

high dimensional functions are conducted in the numpy package which provides the numpy.ndarray data structure

and operations accelerated by vector instructions in hardware.

import numpy as np

def fhatbatched(X_n: np.ndarray, m: float, b: float) -> np.ndarray:

print(f"X_n.shape:{X_n.shape}")

yhat_n = X_n*m+b # vector-scalar multiply and add uses vectorized hardware instructions

return yhat_n

if __name__ == "__main__":

import random

X, Y = np.array([1500, 2100, 800]), [500000, 800000, 250000]

m, b = random.uniform(-3.0, 3.0), random.uniform(-3.0, 3.0)

yhats = fhatbatched(X,m,b) # evaluating fhat on all inputs in one function call

for y, yhat in zip(Y, yhats):

print(f"expected: ${y}, actual: ${yhat:.2f}")

Because the two code snippets seem to have run in relatively the same amount of time, a reasonable question at this point is to ask how much faster is the batched implementation with hardware accelerated vector instructions compared to the vanilla-python sequential implementation?

The answer becomes apparent when the size of vectors is increased.

For instance, when the number of house data in our dataset increases to , , ,

the difference in wallclock time between the two implementations becomes more drastic.

Run the code below which updates n from 3 to 10,000,000 (which will take a few seconds)

in order to measure the difference in wallclock time.

(Note that the construction of dataset Y is omitted to simply compare the evaluation of the sequential and vectorized implementations of .)

import numpy as np

def fhat(x: float, m: float, b: float) -> float: return x*m+b

def fhatbatched(X_n: np.ndarray, m: float, b: float) -> np.ndarray: return X_n*m+b

if __name__ == "__main__":

import random, timeit

X = np.random.rand(10_000_000)

m, b = random.uniform(-3.0, 3.0), random.uniform(-3.0, 3.0)

def sequential(): return [fhat(x,m,b) for x in X]

def vectorized(): return fhatbatched(X,m,b)

scalar_time, vector_time = timeit.timeit(sequential, number=5), timeit.timeit(vectorized, number=5)

print(f"sequential time: {scalar_time:.2f} sec")

print(f"vectorized time: {vector_time:.2f} sec")

Analyzing the two times printed to stdout, the majority if not all of the execution time

was spent waiting for the sequential implementation to complete.

This is because np.ndarray's implementations of * and + are accelerated using

vectorized hardware instructions, which we will implement for ourselves in sections

1.3 Programming High Dimensional Data and Functions and

1.4 Accelerating High Dimensional Functions with the BLAS.

For now, we will continue to use the np.ndarray to carry out the task of price prediction

(even though the specific housing dataset we are working with only has 516 entries.)

1.2.2 Fitting a Line in Higher Dimensions

Before we recover the parameters and which characterize the function that best fits the data, let's increase the expressivity of our function in order to model price not simply as a relation of size but also of the other variables available from the dataset. This means modifying the domain of our function from to so that house price is modeled as a function of form

where is the vector of parameters and so that is the bias. Note that we are now using to denote the size of the feature space rather than slope so that accepts not a scalar but a vector , with the codomain remaining . So for instance, is size, is age, is the number of bedrooms, is the location, each weighted by a parameter indicating how important that feature is relative to the final price. We can still define the batched evaluation over the entire dataset with

where is a data/design matrix which stores vectors in . In Python, this looks like the following:

import numpy as np

def fhatbatched(X_n: np.ndarray, theta: np.ndarray) -> np.ndarray:

print(f"X_n.shape:{X_n.shape}")

yhat_n = X_n@theta # vector-scalar multiply and add uses vectorized hardware instructions

return yhat_n

if __name__ == "__main__":

import random

X, Y = np.array([[1500], [2100], [800]]), [500000, 800000, 250000] # X is (n, m) where n=3, m=1

theta = np.random.uniform(-3.0, 3.0, size=(1,)) # theta is shape (m,)

yhats = fhatbatched(X,theta) # evaluating fhat on all inputs in one function call

for y, yhat in zip(Y, yhats):

print(f"expected: ${y}, actual: ${yhat:.2f}")

1.2.3 The Inductive Principle of Maximizing Likelihood

After the inductive bias on the family of functions has been made, the learning algorithm must find the function with a good fit. Since artificial learning algorithms don't have visual cortex like biological humans2, the notion of "good fit" needs to defined in a systematic fashion. This is done by selecting the parameter which maximizes the likelihood of the data . Returning to the linear regression inductive bias we've selected to model the house price data, we assume there exists noise in both our model (epistemic uncertainty) and data (aleatoric uncertainty), so that where

prices are normally distributed conditioned on seeing the features with the mean being the equation of the line where , then we have that

Returning to the linear regression model, we can solve this optimization with a direct method using normal equations.

def fhatbatched(X_n: np.ndarray, m: float, b: float) -> np.ndarray: return X_n*m+b

if __name__ == "__main__":

X, Y = np.array([1500, 2100, 800]), np.array([500000, 800000, 250000]) # data

X_b = np.column_stack((np.ones_like(X), X)) # [1, x]

bhat, mhat = np.linalg.solve(X_b.T @ X_b, X_b.T @ Y) # w = [b, m]

yhats = fhatbatched(X, mhat, bhat) # yhat

for y, yhat in zip(Y, yhats):

print(f"expected: ${y:.0f}, actual: ${yhat:.2f}")

To summarize, we have selected and computed

- an inductive bias with the family of linear functions

- an inductive principle with the least squared loss

- the parameters which minimze the empirical risk, denoted as

Together, the inductive bias describes the relationship between the input and output spaces, the inductive principle is the loss function that measures prediction accuracy, and the minimization of the empirical risk finds the parameters for the best predictor.

1.2.4 Fitting a Line Directly with Normal Equations

1.2.5 Fitting a Line in Non-Linear Feature Space

Feature Space: polynomials.

1.2.6 Generalization, Bias-Variance Tradeoff and Double Descent

1.2 Programming High Dimensional Data and Functions

Now that we have an operational understanding of how statistical learning employ's the power of the multidimensional array abstraction in practice

with linear regression using the numpy.ndarray, we will now implement our very own version of the multidimensional array which we'll define under teenygrad.Tensor.

1.3.1 The Simplest Tensor Implementation with Nested lists

Let's start with the simplest implementation idea for teenygrad.Tensor,

which is a nested array implementation with Python's built-in list data structure.

For some we will use a float,

for , we will use a list[float],

and for arbitary we will use a list[list[float]].

In fact, this is simply what we started doing in the previous chapter when implementing our linear regression model before switching to numpy's accelerated nd.array.

# teenygrad/__init__.py

def tensor(data) -> Tensor: raise NotImplementedError("")

# teenygrad/tensor.py

class Tensor():

def __init__(self, data): raise NotImplementedError("")

import tinygrad

if __name__ == "__main__":

x = teenygrad.tensor([[1.1, 2.2],

[3.3, 4.4],

[5.5, 6.6]])

1.3.2 Tensors with Strides

strides Mapping Virtual Shapes to Physical Storage

class Tensor():

1.3.2 Tensor.matmul(): Naive Vector/Matrix Operations

class Tensor():

# ...shape, stride, offset, storage

def __matmul__(self):

raise NotImplementedError("")

...

1.3.3 Accelerating Interpreted Language Implementations

1.3.4 CPython Extension Modules via PyO3 and Rust

CPython with Rust Extension Modules via PyO3 <!-- jit: pypy. aot: cython/mypyc. bindings:

two guides

- https://docs.python.org/3/extending/index.html

- https://docs.python.org/3/c-api/index.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=umLZphwA-dw

python c api used for 2 purposes

- extension modules

- embedding cpython cpython native extension modules

pyo3. recommended tools https://docs.python.org/3/c-api/intro.html#c-api-tools

history

- https://www.boost.org/doc/libs/1_58_0/libs/python/doc/

- https://github.com/pybind/pybind11

- https://nanobind.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

- https://github.com/dgrunwald/rust-cpython

https://github.com/PyO3/pyo3/blob/main/Architecture.md

https://github.com/openai/tiktoken https://github.com/huggingface/tokenizers/tree/main/bindings/python https://github.com/pola-rs/polars https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z_Eiy2W0APU

1.3 Accelerating Basic Linear Algebra Subroutines

... talk about BLAS

- 1971 handbook for automatic computation (ALGOL60)

- 1971 EISPACK (FORTRAN66)

- 1973,1974,1975 draft bLAS

- 1979 LINPACK users guide (dongarra, moler) linear systems. linear least squares

- 1979 BLAS1 paper (LINPACK benchmark in appendix)

moore's law -> bell's law mainframes: vector-vector BLAS1 number of loops and the edition minis: matrix-vector BLAS2 number of loops and the edition BLAS2 paper micros: matrix-matrix BLAS3 number of loops and the edition

- http://www.openmathlib.org/OpenBLAS/docs/faq/

- https://dl.acm.org/doi/epdf/10.1145/355841.355847

- https://www.netlib.org/utk/people/JackDongarra/PAPERS/An-Extended-Set-of-BLAS-Model-Implementation-and-Test-Programs.pdf

- https://www.netlib.org/utk/people/JackDongarra/PAPERS/Set-of-Level-3-Basic-Linear-Algebra-Subprograms.pdf

- https://www.cs.utexas.edu/~flame/pubs/GotoTOMS_revision.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JzNpKDW07rw

1.4.1 The SISD Fantasy of Latency-Oriented CPUs

von neumann architecture... ... talk about processor microarchitecture and memory hierarchies

1.4.2 Bottlenecks, Rooflines, and Benchmarks

... talk about bottlenecks (intensity, and rooflines)

ROOFLINES (for computer architectures which look like level 3) compute got cheaper memory hierarchies got deeper minimize surface/volume ratio compute/memory flops are free, bandwidth is money, latency is physics

level3 blas designed for these architectures. thus matmul because arithmetic intensity. is there a blas4? not really.

1.4.3 Accelerating GEMM from Rust to ASM

1.4.4 Accelerating GEMV and GEMM on CPU with Locality

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use std::ops::{Add, Mul}; /// Textbook matrix multiply: C = A @ B /// A is m×k, B is k×n, result C is m×n. /// /// Matrices are row-major Vec<Vec<T>> for readability. pub fn matmul<T>(a: &[Vec<T>], b: &[Vec<T>]) -> Result<Vec<Vec<T>>, String> where T: Copy + Add<Output = T> + Mul<Output = T> + Default, { if a.is_empty() || b.is_empty() { return Err("matmul: empty matrix".into()); } let m = a.len(); let k = a[0].len(); if a.iter().any(|row| row.len() != k) { return Err("matmul: A is not rectangular".into()); } // Ensure B is rectangular let k2 = b.len(); let n = b[0].len(); if b.iter().any(|row| row.len() != n) { return Err("matmul: B is not rectangular".into()); } // Ensure B is rectangular if k != k2 { return Err(format!( "matmul: shape mismatch: A is {}x{}, B is {}x{}", m, k, k2, n )) } let mut c = vec![vec![T::default(); n]; m]; // Allocate C (m×n) filled with zeros (Default::default) // Triple loop: i, j, p for i in 0..m { for j in 0..n { let mut acc = T::default(); for p in 0..k { acc = acc + a[i][p] * b[p][j]; } c[i][j] = acc; } } Ok(c) } }

; matmul_f32(C, A, B, M, N, K)

; SysV ABI args:

; rdi = C

; rsi = A

; rdx = B

; rcx = M

; r8 = N

; r9 = K

;

; row-major:

; A[i*K + k], B[k*N + j], C[i*N + j]

global matmul_f32

section .text

matmul_f32:

push rbx

push r12

push r13

push r14

push r15

1.4.5 Accelerating GEMV and GEMM on CPU with Parallelism

1.5 Learning Sentiment Iteratively with Classification

We'll now tackle our first learning problem in the domain of language with sentiment analysis — classifying whether a given piece of text has a positive or negative connotation — by modifying

- our model to support discrete categorical targets

- our optimization method to an iterative algorithm, namely gradient descent

Before diving into the model to support discrete categorical targets in , we will take a closer look into the optimization method of gradient descent because there are two reasons for why we want to move from direct to iterative methods, the first being memory bottlenecks, and the second being non-linear function classes.

1.5.1 Linear Regression, and the Limitations of Direct Methods

The first reason why we want to switch from direct to iterative optimization methods is because direct methods are memory-bound on materializing the matrix .

1.5.2 Inductive Bias and Principle with Logistic Regression and Cross Entropy

The second reason why we want to switch from direct to iterative optimization methods is because even if the number of dimensions is small enough so that we are not memory-bound, direct methods simply will not work for other function classes besides linear regression. Consider ___.

Inductive Bias

In order to train a model which learns the sentiment of text, we will collect data where the input space are feature vectors and the output space are and which encode the negative and positive cases of binary classification[^6] (we will expand the number of categorical responses in the next section with multi-class classification). Then the function of interest we'd like to recover from the data is of form . Recall that machine learning consists of selecting a family of functions as the inductive bias, a loss function as the inductive principle, and estimating the parameters by empirically minimizing the risk.

For the inputs,

For the model class , we will continue to use a a weighted sum of the input vector with where so that , but add the function where referred to as the logistic or sigmoid[^7] function so that the output is a valid probability. We'll interpret as the log odds and as and the complement as . However, the current type of is , whereas the task is to assign a negative () or positive () sentiment to the provided input feature vector . To ammeliorate this we will add a final decision boundary where

(FIGURE.MODEL ARCHITECTURE)

We can vectorize the evaluation of on each with a data matrix so that

import torch

def f(xi: torch.Tensor, w: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

"""Compute sigmoid(w^T x) for a single example xi."""

logits = torch.matmul(w, xi)

return torch.sigmoid(logits)

if __name__ == "__main__":

w = torch.randn(3)

X = torch.randn(5, 3)

for xi in X: # does this work?

yi_hat = f(xi, w)

print(yi_hat.item())

For example, let's trace through the evaluation of our model with the following input example :

Inductive Principle

For the loss function

1.5.3 Iterative Optimization via Gradient Descent

For estimating the parameters that minimize the loss , we will optimize iteratively using gradient descent, for the two reasons already mentioned of being memory-bottlenecked on materializing the with the linear regression model class, and, with other classes of functions (which is currently the case), we don't have ___.

Gradient descent, simply put, is an optimization method that uses differential calculus, namely, the fact that the gradient provides hints — the direction of steepest descent — on how to iteratively modify the parameters closer to an optimum. The gradient descent algorithm can be expressed in a one line update rule so that the goal of is implemented by:

where is referred to as the learning rate or step size. We now dive deeper into differential calculus and generalize the derivative to higher dimensional spaces[^8] to better understand what's happening under the hood.

1.5.4 Multinomial Logistic Regression

1.5.5 Generalized Linear Models

-

While predicting house prices is not AGI, we follow the canonical hello world of machine learnign in order to provide an easy example while introducing the foundational mechanics of statistical learning, which are crucial to understanding part two and part three of the book where we cover more industrial deep learning. In software 1.0 you should know how to reverse a linked list. In software 2.0 you should know how to fit a line. ↩

-

If you are familiar with functional programming, this is the mathematical equivalent of currying via closure. ↩ ↩2

2. Neural Networks

In part two of the course notes we change both 1. the goal from learning price/sentiment to learning sequences

and 2. the function class from generalized linear models to deep neural networks

with torch to study the foundations of machine learning's "age of research" from 2012 to 2020.

We build off of teenygrad's numpy-like capability developed in part one

and abstract two more tasks for the research scientist

optim.sgdandTensor.backward()providing iterative optimization via differentiationcuBLAS-like kernels providing acceleration on manycore processors like GPUs which we will then use to train other language models with different inductive biases (invariances) such asRNNs,LSTMs,BERTs, andGPTs culminating innanogpt.

This will prepare us for part three of the course notes where we modify the language implementation

of the deep learning framework to support distributed compilation in order to run both

the training and inference of nanochat

Contents

- Representations as Types

- 2.1 Learning Sequences in

torch - 2.2 Programming Automatic Differentiation and Stochastic Gradient Descent with

teenygrad - 2.3 Accelerating

cuBLASKernels withteenygrad - 2.4 Learning Sequences with Different Inductive Biases in

teenygrad

2.1 Learning Representations, Learning Sequences

2.1.1 XOR Learning with Feedforward Neural Network

2.1.2 Sentiment Learning with FNNs

In part 1 of the course notes we trained generalized linear models of the form ___. In part 2 we modify and increase the expressivity of the function class by including non-linearities . The feedforward neural network simply put is a series of linear and non-linear layers of the form so

where , is an elementwise nonlinearity, and . Conceptually, the linear layers are performing linear transformations that rotate, reflect, shear, and scale space, whereas the nonlinear transformations perform transformations that squash and twist space.

We will now use the same model of the feedforward neural network to accomplish two other goals. Namely, representation learning, and sequence learning.

2.1.3 Representation Learning with FNNs

2.1.4 Language Modeling with FNNs

A sequence model, simply put, is the conditional probability distribution of an output token given an input token . A sequence of tokens can be a sentence of words in the domain of language, a series of pixels in the domain of vision, or a stream of waves in the domain of audio.

Since we are modeling language as stochastic phenomena, we use the formal language of probability theory, where a probability space is a measurable space with a measure . In the domain of language, the measurable space consists of a sample space which is the set of all tokens modelling a vocabulary, and the event space is the set of all token combinations which model a language. The measure is the measure of the weight of a particular token combination (sentence, really) as an event with respect to the set of all possible token combinations (sentences) as the entire event space. Once we use a random variable to map events to , we can forget about the probability space and focus our attention on language models which are joint probability distribution over all sequences of tokens.

Language modeling with ngrams.

(1. EXPLAIN MODEL).

# FFN MODEL f: R^n -> R

import torch

class MLP():

"""

model: Neural Language Models (Bengio et al. 2003)

key:

b: batch size, t: sequence length

v: vocabulary size, e: dimension of embedding, d: dimension of model

"""

def __init__(self, cfg):

super().__init__()

b, t, v, e, d = cfg.b, cfg.t, cfg.v, cfg.e, cfg.d

self.wte = layers.Embedding(v+1, e) # token embeddings table (+1 for <BLANK>)

l1 = layers.Linear(t*e, d, b=False)

l2 = layers.Linear(d, d, b=False)

l3 = layers.Linear(d, v, b=False)

def forward(self, i, targets=None):

embs = [] # gather the word embeddings of the previous 3 words

for k in range(self.b):

tok_emb = self.wte(i) # token embeddings of shape (b, t, e)

i = torch.roll(i, 1, 1)

i[:, 0] = self.v # special <BLANK> token

embs.append(tok_emb)

# concat all of the embeddings together and pass through an MLP

x = torch.cat(embs, -1) # (b, t, e * block_size)

x = self.l1(x).tanh()

x = self.l2(x).tanh()

x = self.l3(x)

yhat = x

# if we are given some desired targets also calculate the loss

loss = None

if targets is not None: loss = F.cross_entropy(yhat.view(-1, yhat.size(-1)), targets.view(-1), ignore_index=-1)

return yhat, loss

(2. EXPLAIN DATASET).

# FFN DATA d={(x^i,y^i)}

import torch

import torch.nn.functional as F

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def build_dataset(t):

import random

words = open('./data/names.txt', 'r').read().splitlines()

v = sorted(list(set(''.join(words))))

encode = { c:i+1 for i,c in enumerate(v) }

encode['.'] = 0

decode = { i:c for c,i in encode.items() }

def gen_dataset(words, t):

X, Y = [], []

for w in words:

context = [0] * t

for c in w + '.':

X.append(context)

Y.append(encode[c])

# print(''.join(decode[i] for i in context), '-->', decode[encode[c]])

context = context[1:] + [encode[c]]

X, Y = torch.tensor(X), torch.tensor(Y) # X:(N,C) Y:(N)

return X, Y

random.seed(42)

random.shuffle(words)

n1, n2 = int(0.8*len(words)), int(0.9*len(words))

Xtraining, Ytraining = gen_dataset(words[:n1], t)

Xdev, Ydev = gen_dataset(words[n1:n2], t)

Xte, Yte = gen_dataset(words[n2:], t)

return Xtraining, Ytraining

(3. EXPLAIN TRAINING LOOP).

# FFN TRAINING LOOP: theta^(t+1) := theta^t - alpha*grad(L)

if __name__ == "__main__":

b, t, v, e, d = 32, 3, 27, 10, 200 # init hyperparameters

X, Y = build_dataset(t) # init data

C = torch.randn((v,e), generator=g) # init embedding

model = MLP() # init model

params = [C] + [p for l in model for p in l.parameters()]

for p in params: p.requires_grad = True

N, losses, steps = X.shape[0], [], [] # train

for step in range(200000):

i_b = torch.randint(0, N, (b,))

X_b, Y_b = X[i_b], Y[i_b]

X_bd = C[X_b].view(-1, t * e) # 0. embed

for layer in model: X_bd = layer(X_bd) # 1. forward

loss = X_bd.cross_entropy(Y_b)

for layer in model: layer.out.retain_grad()

for p in params: p.grad = None

loss.backward() # 2. backward

for p in params: p.data += -0.01 * p.grad # 3. update

# optimizer.step()?

steps.append(step)

losses.append(loss.log10().item())

if step % 10000 == 0: print(f"step: {step}/{200000}, loss {loss.item()}")

plt.plot(steps, losses)

In the next two chapters of 2.2 and 2.3, we will implement two features

on picograd which are the two primary tasks which pytorch abstracts away from research scientists:

the backward pass with automatic differentiation, and the device acceleration of the specified forward pass.

2.2 Programming Automatic Differentiation and Gradient Descent

So far we've been training feedforward neural networks using the magical

Tensor.backward() function in order to materialize the gradient of the loss on our

parameter weights which gradient descent uses in it's update rule

.

We will now dive deeper into how .backward() is implemented.

2.2.1 Automatic Differentiation via Tensor.backward()

Consider the function where ,

and translate it to it's computational counterpart in python with one-dimensional `Tensor`s:

import picograd as pg

def f(x1: pg.Tensor, x2: pg.Tensor) -> pg.Tensor:

a = pg.exp(x1)

b = pg.sin(x2)

c = b**2

d = a*c

return d

Figure 1. Python source for the function where

Here we've broken up the function to render the subexpressions more clearly.

But this isn't necessary — automatic differentiation will work if the function was expressed in one line.

In part one, the development of picograd followed that of numpy —

an array programming language similar to Matlab but embedded in the host language of Python,

that could evaluate functions of the form

where Tensor objects stored their values with the value: field

and the function types that produced their values with Op.

For instance, evaluating the specified function f from above with 9 and 10

if __name__ == "__main__":

print(f(9, 10))

populates the Tensor.value fields.

In part one of the book we verified this with a REPL-interface,

but we can also represent the entire expression being evaluated with a

graph of vertices and edges where the vertices are Tensors

(along with their Ops and values) and the edges are their data dependencies:

digraph G {

bgcolor="#181818"; fontname="Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif"

node [

fontname="Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif" fontcolor = "#e6e6e6", color = "#e6e6e6", fillcolor = "#333333"

style = filled,

]

edge [

fontname="Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif"

color = "#e6e6e6",

fontcolor = "#e6e6e6"

]

graph [rankdir="LR"]

x1 [label="9"];

x2 [label="10"];

expx1 [label="a: ℝ -> ℝ\la(x1) := exp(x1)\lval:8103.08, grad:"];

sinx2 [label="b: ℝ -> ℝ\lb(x2) := sin(x2)\lval:-0.54, grad:"];

sqrsin [label="c: ℝ -> ℝ\lc(b) := b^2\lval:-0.30, grad:"];

mulxy [label="d: ℝ, ℝ -> ℝ\ld(a,c) := a*c\lval:-2430.9, grad:"];

x1 -> expx1;

x2 -> sinx2;

sinx2 -> sqrsin

sqrsin -> mulxy;

expx1 -> mulxy;

}

Here you can see that even if the function was specified in one line,

the graph of the expression always parses into Tensor vertices, and data dependency edges.

You may have noticed the Tensor.grad fields, which supposedly store the values of derivatives .

The question now remains in how to populate these fields.

Taking a step back to differential calculus, deriving the derivative of involves the application of the chain rule where . Evaluating the derivative of the function with respect to its inputs and results in

symbolic and numeric differentiattion symbolic differentiation has performance issues since a large unrolled expression must be constructed in order to differentiate[^0], whereas numerical differentiation has correctness issues since evaluating finite differences requires evaluating functions to a precision point resulting in numerical instability. (trace through EXAMPLE for both. talking nets widrow)

To populate the Tensor.grad fields, the simplest idea would be

to literally translate the manual derivation of the derivative into code.

The translation from math to code involves a design decision:

should we evaluate from outputs to inputs (symbolically outside-in, graphically right-to-left) or from inputs to outputs (symbolically inside-out, graphically left-to-right)?

Although the former order seems more natural with symbolic expressions,

there's nothing illegal about the latter.

import picograd as pg

def f(x1: pg.Tensor, x2: pg.Tensor) -> pg.Tensor:

a = pg.exp(x1)

b = pg.sin(x2)

c = b**2

d = a*c

return d

# dict[f(x), f'(x)] of local derivatives (adjoints)

dd_da, dd_dc = [c, a] # d(a,c):=a*c ==> d'(a)=c, d'(c)=a

da_dx1 = pg.exp(x1) # a(x1):=exp(x1) ==> a'(x1)=exp(x1)

dc_db = 2*b # c(b):=b^2 ==> c'(b)=2b

db_dx2 = pg.cos(x2) # b(x2):=sin(x2) ==> b'(x2)=cos(x2)

# outputs to inputs: outside-in symbolically, right-to-left graphically

dd_dd = pg.Tensor(1) # base case

dd_da, dd_dc = [dd_dd*dd_da, dd_dd*dd_dc]

dd_dx1 = dd_da*da_dx1 # DONE for the x1->d path

dd_db = dd_dc*dc_db

dd_dx1 = dd_db*db_dx2 # DONE for x2->path

# inputs to outputs: inside-out symbolically, left-to-right graphically

dx1_dx1, dx2_dx2 = [pg.Tensor(1), pg.Tensor(1)] # base case

da_dx1 = da_dx1*dx1_dx1

dd_dx1 = dd_da*da_dx1 # DONE for the x1->d path

db_dx2 = db_dx2*dx2_dx2

dc_dx2 = dc_dc*db_dx2

dd_dx2 = dd_dc*dc_dx_2 # DONE for the x2->d path

Do you notice any difference in the number of evaluations between the two orders?

The outputs-to-input ordering takes 6 arithmetic operations (including the destructuring),

whereas the input-to-output ordering take 7 arithmetic operations.

This is because the former can reuse dd_dd

as a dynamic programming solution to a subproblem for the two inputs, whereas the latter cannot.

And taking a step back, we only want to reuse the output because the shape of the function

is of . Alternatively, if had type ,

then the input-to-output ordering would be able to reuse results.

This distinction is referred to as "forward-mode" vs "reverse-mode", and reflects

the fact that for some function

the time complexity of forward-mode differentiation is proportional to ,

whereas that of forward-mode differentiation is proportional to .

If the expression graph fans-in so that , reverse-mode is preferred.

If the expression graph fans-out so that , forward-mode is preferred.

However, if we take a step with a graph-theory lens, we can see that the derivative is the sum of paths,

where each path is a product of local derivatives from the input source to the output sink.

From a combinatorics perspective, we are calculating all the possible (ors) ways (ands)

on how the inputs perturb the output. That is:

and as long as the operations along this path are associative — — then we can choose the order in how we perform these path products to minimize the number of operations. Finding the optimal ordering is an NP-hard problem because ____. For instance, if the expression graph is diamond-shaped, evaluating the derivative with forward-mode for the left-half and reverse-mode for the right-half would be more performant. In practice, we use reverse-mode as a heuristic, since most of the functions that are differentiated (so they can be optimized) in the field of machine learning are neural networks of the form

How can we generalize this into an algorithm?

All we need are 1. mappings from and 2. a topological sort

For the derivative rules, the same way that optimizing compilers implement an optimization "manually" once which then gets reused many times, the authors of deep learning frameworks also implement derivatives manually which then become reused many times through automatic differentiation. In theory, we can differentiate any expression with f'(x) with only a few derivative rules for addition and multiplication, but in practice most frameworks provide sugar for complex derivatives.

For topological sort, we can simply reversed the ordering produced by a depth-first-search:

def toposort(self):

order: list[Op] = []

visited: set[Op] = set()

def dfs(node: Op) -> None:

if node in visited: return

visited.add(node)

for src in node.src: dfs(src)

order.append(node)

dfs(self)

return order

class Tensor():

def backward():

for t in reversed(topo):

t.backward()

We will now use this idea to modify the interpretation of our deep learning framework to not only evaluate , but as well. This is done by dynamically overloading the operators at runtime[^0] to trace the expression graph

chain_rules = PatternMatcher([

(Pattern(OpCode.MATMUL, name="input"), lambda output_grad, input: (_____,)),

(Pattern(OpCode.MATVEC, name="input"), lambda output_grad, input: (_____,)),

(Pattern(OpCode.RECIPROCAL, name="input"), lambda output_grad, input: (-output_grad * input * input,)),

(Pattern(OpCode.SIN, name="input"), lambda output_grad, input: ((math.pi/2 - input.src[0]).sin() * output_grad,)),

(Pattern(OpCode.LOG2, name="input"), lambda output_grad, input: (output_grad / (input.src[0] * math.log(2)),)),

(Pattern(OpCode.EXP2, name="input"), lambda output_grad, input: (input * output_grad * math.log(2),)),

(Pattern(OpCode.SQRT, name="input"), lambda output_grad, input: (output_grad / (input*2),)),

(Pattern(OpCode.ADD), lambda output_grad: (1.0*output_grad, 1.0*output_grad)),

(Pattern(OpCode.MUL, name="input"), lambda output_grad, input: (input.src[1]*output_grad, input.src[0]*output_grad)),

])

class Tensor:

def _forward(self, f:Callable, *other:Tensor) -> Tensor: #extra_args=(), **kwargs)

out_tensor = evaluator.eval_uop([self, other], out_uop)

def backward(self, grad:Tensor|None=None) -> Tensor:

"""

backward performs by collecting tensors, computing gradients with automatic differentiation, and updating said tensors.

"""

# 1. collect all tensors that requires grad by topologically sorting the graph of uops and filter

all_uops = self.uop.toposort()

tensors_require_grad: list[Tensor] = [t for tref in all_tensors if (t:=tref()) is not None and t.uop in all_uops and t.requires_grad]

uops_require_grad = [t.uop for t in tensors_require_grad]

assert grad is not None or self.shape == tuple(), "when no gradient is provided, backward must be called on a scalar tensor"

if not (self.is_floating_point() and all(t.is_floating_point() for t in tensors_require_grad)): raise RuntimeError("only float Tensors have gradient")

# 2. compute the gradient with a map of tensors to partials

if grad is None: grad = Tensor(1.0, dtype=self.dtype, device=self.device, requires_grad=False) # base case is 1.0

tens2grads = Tensor._automatically_differentiate(self.uop, grad.uop, set(uops_require_grad)) # skipping materializing zerod grads for now

grads = [Tensor(g, device=t.device) for t,g in zip(tens2grads.keys, tens2grads.values)] # initialize tensor grads on device

# 3. update the tensors that require grad with the gradient's partials

for t,g in zip(tensors_require_grad, grads):

assert g.shape == t.shape, f"grad shape must match tensor shape, {g.shape!r} != {t.shape!r}"

t.grad = g if t.grad is None else (t.grad + g) # accumulate if t.grad exists

return self

@staticmethod

def _automatically_differentiate(root:Op, root_grad:Op, targets:set[Op]) -> dict[Op, Op]:

"""

_differentiate backpropagates partials on a topologically sorted expression graph with the chain rule

and produces the gradient in the form of a map of ops to their partials (which, in turn, are ops)

"""

tens2grads = {root: root_grad}

# 1. topological sort

in_target_path: dict[Op, bool] = {}

for u in root.toposort(): in_target_path[u] = any(x in targets or in_target_path[x] for x in u.src)

dfs = list(root.toposort()) # lambda node: node.op not in {OpCode.DETACH, OpCode.ASSIGN} and in_target_path[node])) # don't flow through DETACH/ASSIGN or anything not in target path

# 2. backpropagation with the chain rule

for tensor in reversed(dfs):

if tensor not in tens2grads: continue

local_grads: tuple[Op|None, ...]|None = cast(tuple[Op, ...]|None, chain_rules.rewrite(tensor, ctx=tens2grads[tensor]))

if local_grads is None: raise RuntimeError(f"failed to compute gradient for {tensor.op}\n\nin {str(tensor)[0:1000]}...")

assert len(local_grads) == len(tensor.src), f"got {len(local_grads)} gradient, expected {len(tensor.src)}"

for tensor,local_grad in zip(tensor.src, local_grads): # <--------------------- MOOOSE: why are we accumulating inside ad()? don't we do it in backward()??

if local_grad is None: continue

if tensor in tens2grads: tens2grads[tensor] = tens2grads[tensor] + local_grad # accumulate if tensor exists

else: tens2grads[tensor] = local_grad # o/w initialize

To implement automatic differentiation with Tensor.backward(),

there is a design decision to be made

— the choice of implementing it dynamically or just-in-time[^3],

similar to the decision of how to implement types for general programming languages[^4].

This stands in contrast to the alternative of performing a just-in-time, source-to-source transformation.

Let's now move onto automatically differentiating the functions of neural networks, specifically the FFN language model from earlier. (johnson/ryan adams ordering) n^2 vs n^3

2.2.2 Stochastic Gradient Descent via optim.sgd

2.3 Accelerating cuBLAS Kernels

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1410.0759

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1804.06826 https://arxiv.org/pdf/2512.02189v1 https://girl.surgery/bad_paper https://www.arxiv.org/pdf/2512.07004

2.3.1 PDP11 Problem: Throughput-Oriented Many Core Processors

#[allow(improper_ctypes_definitions)] #[kernel] pub unsafe fn main_gpu() { println!("of Tensor Programs!"); } use cust::prelude::*; use std::error::Error; fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> { let _ctx = cust::quick_init()?; // Initialize the CUDA Driver API. `_ctx` must be kept alive until the end. let module = Module::from_ptx(PTX, &[])?; // Create a module from the PTX code compiled by `cuda_builder`. let stream = Stream::new(StreamFlags::NON_BLOCKING, None)?; // Create a stream, which is like a thread for dispatching GPU calls. let add_kernel = module.get_function("add")?; unsafe { launch!(add_kernel<<<stream>>>())?; } stream.synchronize()?; Ok(()) }

2.3.2 Accelerating GEMM with CUDA(RS)

2.3.3 Accelerating GEMM with Data Reuse

#[allow(improper_ctypes_definitions)] #[kernel] pub unsafe fn main_gpu() { println!("of Tensor Programs!"); } use cust::prelude::*; use std::error::Error; fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> { let _ctx = cust::quick_init()?; // Initialize the CUDA Driver API. `_ctx` must be kept alive until the end. let module = Module::from_ptx(PTX, &[])?; // Create a module from the PTX code compiled by `cuda_builder`. let stream = Stream::new(StreamFlags::NON_BLOCKING, None)?; // Create a stream, which is like a thread for dispatching GPU calls. let add_kernel = module.get_function("add")?; unsafe { launch!(add_kernel<<<stream>>>())?; } stream.synchronize()?; Ok(()) }

2.3.4 Accelerating GEMM with Scheduling:

#[allow(improper_ctypes_definitions)] #[kernel] pub unsafe fn main_gpu() { println!("of Tensor Programs!"); } use cust::prelude::*; use std::error::Error; fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> { let _ctx = cust::quick_init()?; // Initialize the CUDA Driver API. `_ctx` must be kept alive until the end. let module = Module::from_ptx(PTX, &[])?; // Create a module from the PTX code compiled by `cuda_builder`. let stream = Stream::new(StreamFlags::NON_BLOCKING, None)?; // Create a stream, which is like a thread for dispatching GPU calls. let add_kernel = module.get_function("add")?; unsafe { launch!(add_kernel<<<stream>>>())?; } stream.synchronize()?; Ok(()) }

2.3.5 Accelerating GEMM with Tensor Cores:

2.4 Learning Sequences with Different Inductive Biases

Sequence learning...

2.4.1 CNN: Convolutional Neural Networks

2.4.2 RNN: Recurrent Neural Networks

2.4.3 BERT: Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers

2.4.4 GPT, Generative Pretrained Transformers

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import os, argparse, contextlib

from typing import Optional, Union

with contextlib.suppress(ImportError): import tiktoken

from tinygrad import Tensor, TinyJit, Device, GlobalCounters, Variable, dtypes

from tinygrad.uop.ops import UOp

from tinygrad.helpers import Timing, DEBUG, JIT, getenv, fetch, colored, trange

from tinygrad.nn import Embedding, Linear, LayerNorm

from tinygrad.nn.state import gguf_load, torch_load, load_state_dict, get_state_dict

from extra.bench_log import BenchEvent, WallTimeEvent

MAX_CONTEXT = getenv("MAX_CONTEXT", 128)

HALF = getenv("HALF")

class Attention:

def __init__(self, dim, n_heads):

self.c_attn = Linear(dim, 3*dim, bias=True)

self.c_proj = Linear(dim, dim, bias=True)

self.n_heads = n_heads

self.dim = dim

self.head_dim = dim // n_heads

def __call__(self, x:Tensor, start_pos:Variable, mask:Optional[Tensor]) -> Tensor:

if mask is not None or start_pos.val == 0:

# no symbolic shape qkv when consuming prompts

start_pos = start_pos.val

if HALF: x = x.half()

xqkv = self.c_attn(x).reshape(None, None, 3, self.n_heads, self.head_dim)

xq, xk, xv = [xqkv[:, :, i, :, :] for i in range(3)]

bsz, seqlen, _, _ = xq.shape

# create kv cache

if not hasattr(self, "cache_kv"):

self.cache_kv = Tensor.zeros(2, bsz, MAX_CONTEXT, self.n_heads, self.head_dim, dtype=x.dtype).contiguous().realize()

# update the cache

self.cache_kv[:, :, start_pos:start_pos+seqlen, :, :].assign(Tensor.stack(xk, xv)).realize()

if start_pos > 0:

keys = self.cache_kv[0][:, :start_pos+seqlen, :, :]

values = self.cache_kv[1][:, :start_pos+seqlen, :, :]

else:

keys = xk

values = xv

xq, keys, values = xq.transpose(1, 2), keys.transpose(1, 2), values.transpose(1, 2)

return self.c_proj(xq.scaled_dot_product_attention(keys, values, mask).transpose(1, 2).reshape(bsz, seqlen, self.dim))

class FeedForward:

def __init__(self, dim, hidden_dim):

self.c_fc = Linear(dim, hidden_dim, bias=True)

self.c_proj = Linear(hidden_dim, dim, bias=True)

def __call__(self, x:Tensor) -> Tensor:

return self.c_proj(self.c_fc(x).gelu())

class TransformerBlock:

def __init__(self, dim, n_heads, norm_eps):

self.attn = Attention(dim, n_heads)

self.mlp = FeedForward(dim, 4*dim)

self.ln_1 = LayerNorm(dim, norm_eps)

self.ln_2 = LayerNorm(dim, norm_eps)

def __call__(self, x:Tensor, start_pos:Variable, mask:Optional[Tensor]):

h = x + self.attn(self.ln_1(x), start_pos, mask).float()

return (h + self.mlp(self.ln_2(h))).contiguous()

class Transformer:

def __init__(self, dim, n_heads, n_layers, norm_eps, vocab_size, max_seq_len=1024):

self.vocab_size = vocab_size

self.wte = Embedding(vocab_size, dim)

self.wpe = Embedding(max_seq_len, dim)

self.h = [TransformerBlock(dim, n_heads, norm_eps) for _ in range(n_layers)]

self.ln_f = LayerNorm(dim, norm_eps)

self.lm_head = Linear(dim, vocab_size, bias=False)

self.forward_jit = TinyJit(self.forward)

def forward(self, tokens:Union[Tensor,UOp], start_pos:Variable, temperature:float=0.0):

if not hasattr(self, 'allpos'): self.allpos = Tensor.arange(0, MAX_CONTEXT).reshape(1, -1).realize()

if isinstance(tokens, UOp):

seqlen = 1

tok_emb = self.wte.weight.shrink(((tokens, tokens+1), None))

else:

seqlen = tokens.shape[1]

tok_emb = self.wte(tokens)

# not symbolic when consuming the prompt

selected_pos = (0, seqlen) if start_pos.val == 0 else (start_pos, start_pos+1)

pos_emb = self.wpe(self.allpos.shrink((None, selected_pos)))

h = tok_emb + pos_emb

if HALF: h = h.half()

mask = Tensor.full((1, 1, seqlen, start_pos.val+seqlen), float("-inf"), dtype=h.dtype).triu(start_pos.val+1) if seqlen > 1 else None

for hi in self.h: h = hi(h, start_pos, mask)

logits = self.lm_head(self.ln_f(h))

if logits.shape[1] == 0:

# special case for empty prompt

logits = Tensor.ones((logits.shape[0], self.vocab_size), dtype=logits.dtype, device=logits.device)

else:

logits = logits[:, -1, :]

if temperature < 1e-6:

ret = logits.argmax(-1)

else:

ret = (logits / temperature).softmax().multinomial()

return ret.flatten().realize()

def __call__(self, tokens:Union[Tensor,UOp], start_pos:Variable, temperature:float=0.0) -> Tensor:

forward = (self.forward_jit if JIT and (isinstance(tokens, UOp) or tokens.shape[1] == 1) else self.forward)

return forward(tokens, start_pos, temperature)

3. Scaling Networks

age of scaling (2020 - 2025)

Contents

- 3.1 Scaling Large Language Models

- 3.2 Accelerating

nanogptwith FlashAttention - 3.3 Programming a Compiled and Distributed

Tensor

3.1 Scaling Large Language Models

3.2 Accelerating nanogpt with FlashAttention

3.2 Programming a Compiled and Distributed Tensor

3.2.1 OpCode, OpNode Intermediate Graph Representation

3.2.2 ExecItem Kernelizer/Fuser, Scheduler

3.2.3 Runtime, Allocator, Heterogenous Runtime

Afterword

To continue deepening your knowledge, the following courses are a good next step. You might find this book complementary to your reading, since the two streams were woven into a single narrative for the book. Once you feel comfortable, you should graduate towards contributing to larger machine learning systems.

Good luck on your journey. I'll see you at work.

Teenygrad/Tinygrad Abstraction Correspondance

| Teenygrad | Tinygrad | Notes |

|---|---|---|

OpNode | UOp | Expression graph vertices |

OpCode | Ops (enum) | Operation types |

Buffer | Buffer | Device memory handles |

Runtime | Compiled (Device class) | Memory + compute management |

Allocator | Allocator | Buffer allocation/free |

Compiler | Compiler | Source → binary compilation |

Generator | Renderer | IR → source code generation |

Kernel | Program (CPUProgram, CUDAProgram) | Executable kernel wrapper |

Recommend Resources

Tensor Programming

Recommended Books

- Speech and Language Processing by Jurafsky and Martin

- The Elements of Statistical Learning by Friedman, Tibshirani, and Hastie

- Deep Learning by Goodfellow, Bengio and Courville

- Reinforcement Learning by Sutton and Barto

- Probabilistic Machine Learning by Kevin Murphy

Recommended Lectures

- UPenn STAT 4830: Numerical Optimization for Machine Learning by Damek Davis

- MIT 18.S096: Matrix Calculus by Alan Edelman and Steven Johnson

- Stanford CS124: From Languages to Information by Dan Jurafsky

- Stanford CS229: Machine Learning by Andrew Ng

- Stanford CS230: Deep Learning by Andrew Ng

- Stanford CS224N: NLP with Deep Learning by Christopher Manning

- Eureka LLM101N: Neural Networks Zero to Hero by Andrej Karpathy

- Stanford CS336: Language Modeling from Scratch by Percy Liang

- HuggingFace: Ultra-Scale Playbook: Training LLMs on GPU Clusters

Tensor Interpretation and Compilation

Recommended Books

- Structure and Interpretation of Tensor Programs by j4orz

- Programming Massively Parallel Processors by Hwu, Kirk, and Hajj

- Computer Architecture: A Quantitative Approach by Hennessy and Patterson

Recommended Lectures

- CMU 10-414/714: Deep Learning Systems by Tianqi Chen and Zico Kotler

- MLC: Machine Learning Compilers by Tianqi Chen

- MIT 6.172: Performance Engineering by Saman Amarasinghe, Charles Leiserson and Julian Shun

- MIT 6.S894: Accelerated Computing by Jonathan Ragan-Kelley

- Berkeley CS267: Applications of Parallel Computers by Katthie Yellick

- UIUC ECE408: Programming Massively Parallel Processors by Wen-mei Hwu

- Stanford CS149: Parallel Computing by Kayvon Fatahalian

- Stanford CS217: Hardware Accelerators for Machine Learning by Ardavan Pedram and Kunle Olukotun

- Carnegie Mellon 18-447: Computer Architecture by Onur Mutlu

- Carnegie Mellon 18-742: Parallel Computer Architecture by Onur Mutlu

- ETH 227: Programming Heterogeneous Computing Systems with GPUs by Onur Mutlu

Bibliography

- Austin et al., "How to Scale Your Model", Google DeepMind, online, 2025.

- Ansel et al. 2024. “PyTorch 2: Faster Machine Learning through Dynamic Python Bytecode Transformation and Graph Compilation.” ACM, April.

- Baydin et al. 2015. “Automatic Differentiation in Machine Learning: A Survey.” ArXiv.org

- Bakhvalov, Denis. Performance Analysis and Tuning on Modern CPUs. 2024.

- Bright, Paige, Alan Edelman, and Steven G Johnson. 2025. “Matrix Calculus (for Machine Learning and Beyond).” ArXiv.org

- Bryant, Randal E, and David R O’hallaron. 2016. Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective. Boston: Pearson Education.

- Blondel, Mathieu, and Vincent Roulet. 2024. “The Elements of Differentiable Programming.” ArXiv.org

- Boehm, Simon. 2022. “How to Optimize a CUDA Matmul Kernel for cuBLAS-like Performance: A Worklog.” Siboehm.com

- Chen, Tianqi, Thierry Moreau, Ziheng Jiang, Lianmin Zheng, Eddie Yan, Meghan Cowan, Haichen Shen, et al. 2018. “TVM: An Automated End-To-End Optimizing Compiler for Deep Learning.” ArXiv, February.

- Fog, Agner. “Software Optimization Resources. C++ and Assembly. Windows, Linux, BSD, Mac OS X.” Agner.org.

- Goodfellow, Ian, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville. 2016. Deep Learning. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- Griewank, Andreas, and Andrea Walther. 2009. Evaluating Derivatives: Principles and Techniques of Algorithmic Differentiation. Philadelphia, Pa.: Society For Industrial & Applied Mathematics ; Cambridge.

- Hastie, Trevor, et al. The Elements of Statistical Learning, Second Edition : Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction. 2nd ed., New York, Springer, 2009.

- Hennessy, John L, and David A Patterson. 2025. Computer Architecture: A Quantitative Approach. Cambridge, Ma: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Hwu, Wen-Mei W, David B. Kirk, and Izzat El Hajj. 2022. Programming Massively Parallel Processors: A Hands-on Approach. S.L.: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Jurafsky, Dan, and James H. Martin. 2025. “Speech and Language Processing.” Stanford.edu. 2025.

- Murphy, Kevin P. 2023. Probabilistic Machine Learning: Advanced Concepts. MIT Press.

- Murphy, Kevin P. 2022. Probabilistic Machine Learning: An Introduction. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Paszke, Adam, Sam Gross, Francisco Massa, Adam Lerer, James Bradbury, Gregory Chanan, Trevor Killeen, et al. 2019. “PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library.” ArXiv.org

- Ragan-Kelley, Jonathan, Connelly Barnes, Andrew Adams, Sylvain Paris, Frédo Durand, and Saman Amarasinghe. 2013. “Halide.” Proceedings of the 34th ACM SIGPLAN Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation.

- Shankhdhar, Pranjal. 2025. “Outperforming cuBLAS on H100: A Worklog.” 2025.

- Suhan, Alex, Davide Libenzi, Ailing Zhang, Parker Schuh, Brennan Saeta, Jie Young Sohn, and Denys Shabalin. 2021. “LazyTensor: Combining Eager Execution with Domain-Specific Compilers.” ArXiv.org

- Sutton, Richard S, and Andrew Barto. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. 2nd ed., Cambridge, Ma ; London, The Mit Press, 2018.

- Tazi et al., "The Ultra-Scale Playbook: Training LLMs on GPU Clusters", 2025.

- Uwe Naumann. 2012. The Art of Differentiating Computer Programs: An Introduction to Algorithmic Differentiation. Philadelphia: Society For Industrial And Applied Mathematics.